|

|

|

The Order of St.John

![]()

History of the Order, unofficial website

Comprehensive, definitive; Official Hospitiler site with sources & pics

**Historically these events denote conflict between Islam and Christianity. They are displayed as a record of events that happened in a time where religious tolerence was far below what should be expected today. The Order of the Knights Hospitiler have renounced Military activity and exist as an humanitatian organisation.**

The background to the Military Orders

As the growth of Islam caused the boundaries of the Byzantine empire to shrink, the Basileus, Alexius II Comnenus, keen to prevent further incursions into his territory, and also wanting the minimum harm to his own subjects, decided that the best solution was to offer cash to the barbarians in the west to do the job for him. He appealed for mercenaries, but was rather surprised by the result. Pope Urban II, keen to increase his power, and stop the Franks from fighting each other, and jealous of the position of the Basileus as a temporal and spiritual ruler, re-interpreted the invitation. He offered the westerners land, guaranteed passage to Heaven, and indulgences, if they re-captured Jerusalem as a Roman catholic state, not a Byzantine one. The first Crusade eventually succeeded in the Papal aim, and Jerusalem was captured by Frankish Knights in 1100.The Frankish Kingdom of Jerusalem was held for about two centuries, and one of the reasons for this was the formation of new Religious orders, which vastly strengthened the Frankish forces. These were warrior monks, the Knights of the Temple and the Knights of the Hospital, who, initially began by protecting western pilgrims to the shrine of the Holy Sepulchre, living by a monastic code based upon the Rule of St. Benedict. These warriors became an elite fighting force, disciplined, deadly, and inspired by the zeal of religious fanaticism.

The Crusader kingdoms in the Holy Land lasted until 1291, largely thanks to the immense fortifications raised by the Templars and Hospitilars. The greatest of these was Krac de Chevaliers. The reputation of the knights in battle ensured that any knights captured by Muslims were always executed, rather than ransomed. However, the distance from Western Europe, the pressure from Muslim forces, and the skill of leaders such as Saladin eventually decimated the military integrity of the Crusader Kingdoms, and not even the Third Crusade succeeded in bolstering what was left. The Knights Hospitilar were forced to leave the Holy Land, although they did not give up without a fight. They settled on Cyprus, weak in numbers and with the Grandmaster wounded. As they built up their strength in the Frankish possession, they began to feel the need for their own independent headquarters.

The Knights in Rhodes

Eventually Grandmaster Foulques de Villaret negotiated Rhodes from the Frankish ruler of the Dodecanese, and captured the island and its neighbours from its Greek inhabitants by 1309. A Byzantine town and castle were fortified, and the Order dedicated itself to ensuring the security of their possessions, and conducting raids on Muslim ports and general piracy.

The Order of the Knights

Hospitilar of St. John were a truely multinational force. It was comprised of

factions, Langues or Tongues of Knights from the Latin

Kingdoms of E urope:

Provence, Auvergne, France, Italy, Arragon, England, Germany and Castille. Each

Langue elected an Officer (Pileri) to head them, and hold one of the major

offices of the Order, such as the

Grand Hospitaler, in charge of the Hospital, the centre of the Knight's mission.

From these ranks came the Grand Master, the elected head of the order,

answerable only to the Roman Pontiff. The defence of the citadel of the Knights

in Rhodes was divided between the Langues, each taking responsibility for a

portion of the perimeter of the city; the Knights of England commanded the

double-moted portion on the right of the image above. The Knights had to take

quasi-monastic vows, and had to come from noble families. The Order was also

comprised of Chaplains and Sergeants.

urope:

Provence, Auvergne, France, Italy, Arragon, England, Germany and Castille. Each

Langue elected an Officer (Pileri) to head them, and hold one of the major

offices of the Order, such as the

Grand Hospitaler, in charge of the Hospital, the centre of the Knight's mission.

From these ranks came the Grand Master, the elected head of the order,

answerable only to the Roman Pontiff. The defence of the citadel of the Knights

in Rhodes was divided between the Langues, each taking responsibility for a

portion of the perimeter of the city; the Knights of England commanded the

double-moted portion on the right of the image above. The Knights had to take

quasi-monastic vows, and had to come from noble families. The Order was also

comprised of Chaplains and Sergeants.

As the Ottoman Turks conquered more and more Byzantine land, finally taking Constantinople itself in 1453 and then down into Greece, Rhodes became an ever-more isolated bastion of Christendom in an Islamic world. The stubborn militancy of the Knights, and the impudence of their raids could achieve eventually led Sultan Mehmet II to launch a campaign against them. 23rd May-17th August saw the first siege of Rhodes by 100,000 Turks. The massive siege, however, failed; although the walls were breached, the Knights' counter-attack led them up to the Turkish camp, and the sacking of the commander's own tent, which brought the siege to an end.

However on 26th June 1522, the Turks returned with 200,000 men, and under the orders of Sultan Sulieman the Magnificent, who was to later arrive in person. The siege ran on for months, thousands of Turks each day falling in the massive dry moats, deliberate "killing ground" in front of the stout bastions of the Knights and their Greek garrison, and their many cannon. Some days, such as the 24th September, saw Turkish attacks leave as many as 15-20,000 Turks killed, to about 200 dead and 150 wounded Knights. Following such losses, the Sultan decided to raise the siege, and was stopped only by the treachery of Grand Chancellor d'Amaral, who conveyed a message stressing the lack of supplies and men in the city. Despite this, (and the execution of d'Amaral, the city did not fall for another couple of months. Eventually, Grandmaster Phillipe Villiers de L'Isle Adam, for the sake of the Rhodian citizens, finally agreed to terms that would see the Greeks safe, and the Knights allowed to depart with anything that they could carry. On the 1st January 1453, the Knights and c.4500 Rhodians left their shattered fortress after 213 years.

The Knights in Malta

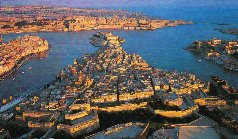

The Knights went to Italy, and the

Grandmaster begged aid from the Courts of Europe, seeking first to re-take

Rhodes, and as this became less likely, to find a new base. In 1530, they

eventually decided to rent Malta from the Spanish Emperor Charles V, and quickly

fortified an area of large natural harbours on the barren and otherw ise

unpromising-looking island. The early towns of Birgu and Senglea echo the

winding cobbled streets of Rhodes, as the homesick Knights enclosed them with

their massive moats and walls. Originally intended as a temporary home, the

Knights soon found that Malta allowed them to intercept the major Turkish

shipping routes between North Africa and Asia Minor. Knights' Galleys could

descend on ships and ports without the easy detection that went with an island

just off the Turkish coast. They began to inflict real damage to Turkish trade,

so much so, that Sultan Sulieman, cursing the fact that he had allowed the

Knights to escape him before, assembled the largest fleet the Mediterranean had

seen to wipe them out once and for all.

ise

unpromising-looking island. The early towns of Birgu and Senglea echo the

winding cobbled streets of Rhodes, as the homesick Knights enclosed them with

their massive moats and walls. Originally intended as a temporary home, the

Knights soon found that Malta allowed them to intercept the major Turkish

shipping routes between North Africa and Asia Minor. Knights' Galleys could

descend on ships and ports without the easy detection that went with an island

just off the Turkish coast. They began to inflict real damage to Turkish trade,

so much so, that Sultan Sulieman, cursing the fact that he had allowed the

Knights to escape him before, assembled the largest fleet the Mediterranean had

seen to wipe them out once and for all.

The Great Siege

The Knights strenghtened their defences, and Grandmaster Jean de la Vallette recalled his brethren from around Europe to the defence of their convent. On 19/5/1565, Sulieman's fleet, the largest that the Mediterranean had seen, arrived; 181 ships and 40,000 troops, including 4,000 crack Janissaries, against the 600 Knights and 9,000 Maltese who had made it ti Malta. The Turks landed their forces, deploying their manpower out of reach of the Knights' guns, and planning their next move. However, their was indecision over how to continue: the Turkish general thought that the weaker, old capital of Mdina should be taken first, although the Admiral, who had joint command, wanted to ensure that the fleet was anchored safely. The vast natural deep-water harbour of Marsamascetto was the obvious choice, being sheltered from the Knights' main strongholds of Birgu and Senglea from the rocky mound of Mount Scebberas. All that prevented their entrance was the small, hastily constructed star-shaped fortification of Fort St.Elmo, which guarded the entrances to both Grand Harbour and Marsamuscetto. The Turkish engineers surveyed this small impediment, and decided that three days would see the fort fall, the fleet anchored, and the main assault ready to begin. This was the greatest mistake of the siege for although St. Elmo was small, it was to cost the Turks heavily; for St.Elmo was to hold out for thirty days, and its small garrison would cost the Turks some 8,000 of their best men.

St.Elmo's strength was in the fact that while it could be attacked from the sea and the slopes of Mount Scebberas, it could also be relieved by the Knights from Birgu. Every night, rowing boats would cross the Grand Harbour, and fresh troops would replace those too badly wounded to continue. Fort St.Elmo had been constructed, albeit quickly, to the latest military innovation and specification, allowing few defenders to hold it against a much larger force. It was designed minimise the effects of hostile artillery fire, whilst maximising the firepower of the defenders, making use of a wide killing ground that had to be crossed by any attackers. Wave after wave of troops, including Janisseries, were repelled, although the near-continual bombardment began to take its toll on the shattered bastions. Turkish dead filled up the dry moat, Janissaries giving up their lives to allow their comrades to use their bodies as a bridge to top the wars. Late to arrive, the formidable Corsair Dragut, appointed by the Sultan as Turkish Supreme commander, saw the folly of the attack on St.Elmo, realising that a massive effort and loss would be rewarded by only the weakest of the key Hospitilar fortification falling.

However Dragut felt that since they

were committed, he could do nothing other than see the action through, and

set-about increasing the ferocity of the attack. St.Elmo's days we re

numbered; Dragut hauled guns and boats across Mount Scebberas to pound the

walls into submission. Soon the only way that the defenders could move about the

fort was by crawling next to the outside walls, as the trajectory of the

attacking guns prevented freedom of movement inside the walls. A deputation was

made by one of the younger Knights to the Grandmaster, urging the evacuation of

St.Elmo to preserve the lives of the garrison, as it was felt that the fort

could not be held much longer. The seventy-year old Vallette greeted the news

with disdain; he bolstered morale with resolute action; he offered boats for any

Knights and Maltese who were "afraid" to stay in St.Elmo any longer,

offering to pack them with the willing volunteers in Birgu and Senglea who were

eager to hold St.Elmo to the last and cost the enemy dearly. The deputation,

seeing the enthusiasm of their comrades, were shamed and inspired; nobody left

the fort. Despite the death of Dragut, resulting from shrapnel, the additional

firepower from the Turkish forces served to stop the nightly "blood

transfusion" to St.Elmo, and the fort's days were truely numbered. By

the final day, there was nobody left free from wounds, and the garrisson

commanders could no longer stand and fight. As the Janisseries gathered for

their final storm, the Knight commanders had chairs set-up inside the breach, so

that they could die fighting, wielding their broadswords. St.Elmo finally fell;

still burning that night, the intensity of the blaze lit the area. The garrison were

slaughtered, the dead Knights and priests lashed to crosses, and set afloat in

Grand Harbour, so that the morning tide washed them up under the walls of Birgu

and Senglea. Vallette retaliated; his Turkish prisoners were beheaded, and the

guns of the Knights fired the heads back to the Turks. By this unprecedented

action, Vallette made a bold statement to both the Turks and his own people:

there would be no quarter here as there was on Rhodes; St.Elmo would be nothing

before the might of the walls Birgu, Fort St.Michael and Fort St.Angelo.

re

numbered; Dragut hauled guns and boats across Mount Scebberas to pound the

walls into submission. Soon the only way that the defenders could move about the

fort was by crawling next to the outside walls, as the trajectory of the

attacking guns prevented freedom of movement inside the walls. A deputation was

made by one of the younger Knights to the Grandmaster, urging the evacuation of

St.Elmo to preserve the lives of the garrison, as it was felt that the fort

could not be held much longer. The seventy-year old Vallette greeted the news

with disdain; he bolstered morale with resolute action; he offered boats for any

Knights and Maltese who were "afraid" to stay in St.Elmo any longer,

offering to pack them with the willing volunteers in Birgu and Senglea who were

eager to hold St.Elmo to the last and cost the enemy dearly. The deputation,

seeing the enthusiasm of their comrades, were shamed and inspired; nobody left

the fort. Despite the death of Dragut, resulting from shrapnel, the additional

firepower from the Turkish forces served to stop the nightly "blood

transfusion" to St.Elmo, and the fort's days were truely numbered. By

the final day, there was nobody left free from wounds, and the garrisson

commanders could no longer stand and fight. As the Janisseries gathered for

their final storm, the Knight commanders had chairs set-up inside the breach, so

that they could die fighting, wielding their broadswords. St.Elmo finally fell;

still burning that night, the intensity of the blaze lit the area. The garrison were

slaughtered, the dead Knights and priests lashed to crosses, and set afloat in

Grand Harbour, so that the morning tide washed them up under the walls of Birgu

and Senglea. Vallette retaliated; his Turkish prisoners were beheaded, and the

guns of the Knights fired the heads back to the Turks. By this unprecedented

action, Vallette made a bold statement to both the Turks and his own people:

there would be no quarter here as there was on Rhodes; St.Elmo would be nothing

before the might of the walls Birgu, Fort St.Michael and Fort St.Angelo.

<above> Fort St. Elmo, with the later citadel of Valletta, built on mt.Scebberas, behind.

With St.Elmo destroyed, the Turkish fleet was able to anchor, and more guns were dragged up along Mt.Scebberas to begin their murderous bombardment accross Grand Harbour to Fort St. Angelo and Senglea. The Turkish land forces closed in upon the landward sides of the cittadels of the Knights. The Grandmaster's only hope of survival was for the aid he had requested from the Spanish Viceroy of Sicily, Malta being rented from the Spanish Emperor Charles V. Viceroy Garcia de Toledo had promised to come to the aid of the Knights once he had assembled a sufficient force. However, he hesitated: it was a reasonable assumption that if the Turks were successful, their next target might well be Sicilly, as a preliminary to an invasion of Europe. The armies of Sulieman had reached and been halted at the walls of Vienna; Garcia de Toledo would need all of his troops to defend his own demesne, as it seemed inevitable that the Knights could not survive the conflict. He had replied to Vallette that he would send relief if the Knights could send their gallies to bring in the Spanish troops. Vallette had pointed out, via Maltese messengers who broke the naval blockade at night in rowing boats, that he could not get a warship past the blockade; the majority of the Knights' ships had been carefully sunk in the creeks between Birgu and Senglea for protection, or sailed to Sicily anyway. Garcia did, however, have more persuasion from the Knights who had not made it to Malta on time; the remaining gallies, and Knights from accross Europe had assembled on Sicily, and were desperate to sail for Malta; if there Order was to die in the final defence of their Convent, then they were desperate to die with it. This pressure kept Don Garcia aware of the fact that he might well have to act. One ship of Knights was able to break the blockade as St.Elmo fell; they landed near Birgu and were ferried by rowing-boats accross Kalkara Creek to Birgu, their banners announcing to the Turks that by morning re-enforcements, (albeit few) had got through.

The Assault on Birgu

<below> the assault on Senglea (left) guarded by Fort St. Michael, with Birgu (right) Fort St. Angelo at the rear. Mt.Scebberas is behind, St.Elmo on the far right.

The Turkish assault on Birgu and Senglea

comprised of a massive artillery bombardment, from all sides. Finally, after wee ks of murderous fire, and the occasional (largely unsuccessful attack)

the Turks gained a near success; two attacks were timed to hit Fort St.Michael,

the forward defence of Senglea first, and once the defenders had moved to repel

it, a second force would hit Birgu. The Turks were able to breach the moat of

Birgu and storm the bastions. The Grandmaster himself, racing from his

headquarters with minimal armour, and a hastily grabbed sword, led his reserve

in person to repel the attackers; receiving a head-wound in the struggle, his

presence served to rally his panicked troups and hold the tied. Evens so,

carefully pressed assault could have seen the Turks in the citadel; but reports

among them turned the attack into retreat: a relief force had landed and was

attacking the Turkish camp and baggage! As the army returned to camp in haste,

the truth was revealed. This was no relief force, but the cavalry from Mdina who

had sallied forth and attacked the Turkish baggage, before retreating in front

of the returning force and returning to their overlooked stronghold. The

situation was not to improve for the Knights; although they held onto their

walls by a margin, time was running out. Landward and seaward attacks were

repelled, but the number of wounded grew, and there were no more reserve troops.

ks of murderous fire, and the occasional (largely unsuccessful attack)

the Turks gained a near success; two attacks were timed to hit Fort St.Michael,

the forward defence of Senglea first, and once the defenders had moved to repel

it, a second force would hit Birgu. The Turks were able to breach the moat of

Birgu and storm the bastions. The Grandmaster himself, racing from his

headquarters with minimal armour, and a hastily grabbed sword, led his reserve

in person to repel the attackers; receiving a head-wound in the struggle, his

presence served to rally his panicked troups and hold the tied. Evens so,

carefully pressed assault could have seen the Turks in the citadel; but reports

among them turned the attack into retreat: a relief force had landed and was

attacking the Turkish camp and baggage! As the army returned to camp in haste,

the truth was revealed. This was no relief force, but the cavalry from Mdina who

had sallied forth and attacked the Turkish baggage, before retreating in front

of the returning force and returning to their overlooked stronghold. The

situation was not to improve for the Knights; although they held onto their

walls by a margin, time was running out. Landward and seaward attacks were

repelled, but the number of wounded grew, and there were no more reserve troops.

The situation was not good for the Turks either; prior to their arrival on Malta, the Knights had poisoned the wells and destroyed their crops. Unlike Rhodes, Malta was rocky and barren. The Turks could not live off the land, and were suffering from the massive casualties they had received. Dysantry was rife, and morale was, by now, very low. The summer was ebbing away, and the Mediterranean was not good in the autumn and winter. The Turks needed a victory soon, as wintering on an inhospitable island was not an option, especially if a relief force could sail from nearby Sicily. A half hearted attempt to subdue Mdina failed; the Grand Marshall, custodian of the citadel had the city's women join their few soldiers on the ramparts, and wasted gunpowder by firing on the too-distant Turks, to feign a full compliment of troops and more than enough ammunition. The bluff worked, and with the continued threat of Mdina's cavalry to harass the camp, Turkish morale so much that when a fleet was sighted heading from Sicily they took what was an excuse to leave, and began embarking on their galleys, and making ready to raise the siege.

Turkish troops were already boarded as the relief force aproached Malta from the Northwest, and then the Turks realised their mistake; the relief force was tiny, a few galleys of Knights and some Spanish mercenaries. Don Garcia's troops were as few as he could get away with sending, and even so, had come on the understanding that they would only land if St. Elmo still stood. The Knights were able to trick them, and claimed that St. Elmo still stood; the relief force landed at St.Paul's bay, and the Knights spread out on unfavourable ground in their eagerness to fight their enemy before their enemy fled. When the Turkish leaders saw the contemptible size of the Relief force, they ordered their troops back out of the ships, to destroy the opposition. However, this was the final straw for the demoralised army. The Knights charged them, and their enthusiasm made up for their small numbers. Vallette ordered his troops out of their fortress, and the Cavalry emerged from Mdina. What was left of the Turkish army raced for their ships, and the crippled fleet limped from Malta. On the 7th September, Malta was free.

Valletta

Such was the destruction, that a mere

quarter of the fleet returned to Constantinople, 10,000 out of 40,000 troops, and Sultan Sulieman

w as forced

to order his decimated

army to sail up the Golden Horn at night to hide their defeat, claiming that his

sword was only invincible when wielded by his own person. The Spanish

troops arrived in greater numbers to

protect the walls of Birgu and Senglea once the enemy had gone, and the West

rejoiced in the valour of the Knights. Plans were immediately

drawn up to repair the damage, and Vallette decreed that a new fortress would be

built for the Knights along the strategic top of Mt. Scebbaras. Gold flooded

into the coffers of the Order, and the Papal architect came to Malta to plan a

new city which would resist any more attacks that would come from the Turks.

Built under the protection of 15,000 Spanish troops, the foundation stone was

laid on 28/3/1566; completed after the death of Vallette,

the city was to bear his name: the Humble City of Vallette, "Humillima

Civitas Vallettae", Valletta. Birgu and Senglea were restored, and

re-named: Senglea became Invitta, "the unconqured", while Birgu became

"The Victorious City", Vittoriosa.

as forced

to order his decimated

army to sail up the Golden Horn at night to hide their defeat, claiming that his

sword was only invincible when wielded by his own person. The Spanish

troops arrived in greater numbers to

protect the walls of Birgu and Senglea once the enemy had gone, and the West

rejoiced in the valour of the Knights. Plans were immediately

drawn up to repair the damage, and Vallette decreed that a new fortress would be

built for the Knights along the strategic top of Mt. Scebbaras. Gold flooded

into the coffers of the Order, and the Papal architect came to Malta to plan a

new city which would resist any more attacks that would come from the Turks.

Built under the protection of 15,000 Spanish troops, the foundation stone was

laid on 28/3/1566; completed after the death of Vallette,

the city was to bear his name: the Humble City of Vallette, "Humillima

Civitas Vallettae", Valletta. Birgu and Senglea were restored, and

re-named: Senglea became Invitta, "the unconqured", while Birgu became

"The Victorious City", Vittoriosa.

After its completion, Sulieman sent spies to assess Valletta's defences, in view of a follow-up attack. Looking at the MASSIVE bastions, and multiple moats, they returned with the simple message: "don't bother!"

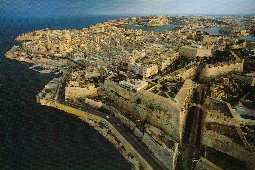

<above> The awesome fortifications of Valletta. This is just the inner moat,

there's a lot to get past before you get this far! Note the size of the white

car on the road below. These walls were used as the walls of Rome in the epic Gladiator.

The city of Valletta was built so well that it has never been taken in battle, and the massive walls, tunnels and bastions proved to be so strong that they sheltered British and Maltese citizens from Italian and Luftwaffe bombs during the second World War, with standing direct hits from bombing more intense than the blitz in London. But that's another story....

Next time: The Knights on Malta and beyond......

I'm endebted to the masterly work "The Great Siege" by Ernle Bradford for the potted history of the siege. I've followed the sequence of events laid down by him, but from memory, so as not to intentionally cite his material. Its a danm good book, go and get a copy!!